Dr. Phil as Executioner

Published 3.19.19

Kim: “And where do you think the curiosity came from?… Little girls don’t think about strip teasing, little girls don’t think about doing anything like that unless they’re taught it.”

Bob: “I didn’t teach you how to strip tease, you showed me, you were doing it in front of me.”

Kim: “You showed me porn videos!"

Bob: “One.”

Phil: “What are you doing showing your daughter a porn video?”

Bob:“It wasn’t a big deal, I mean…”

Dr. Phil: “Anytime a father is showing their minor daughter a pornographic video, that’s a big deal.”

This is a quote from the episode of Dr. Phil that aired on February 27 2018; Kim had requested for Dr. Phil’s assistance in confronting her father, who had molested her for 7 years (from 7 - 14), coerced her to perform sexual acts, shown her pornographic videos, and told her that any mention of this to someone else would ensure she went to prison along with her father. The father, Bob, didn’t deny that he molested his daughter, but instead insisted that it wasn’t his fault, because he always had given her a choice to have sex with him or not, and never physically forced himself upon her.

In the entire episode, there is a type of “war” going on; Bob is deemed as a criminal, and he is constantly trying to escape from that identity by interpreting the situation differently, but at every turn, Dr. Phil “kills” this identity. Instead of allowing Bob’s interpretation, that this was a consensual relationship between two people, to take hold of the show, or to appear as reasonable, Dr. Phil constantly puts it to “death.” Dr. Phil, then, is an executioner.

Is that just a metaphor? No, I think there’s more to it. In my view, the similarities run much deeper, and there’s a lot to be gained by looking at Dr. Phil as a kind of modern day scaffold. In order to show this though, we have to turn to source from a completely different domain.

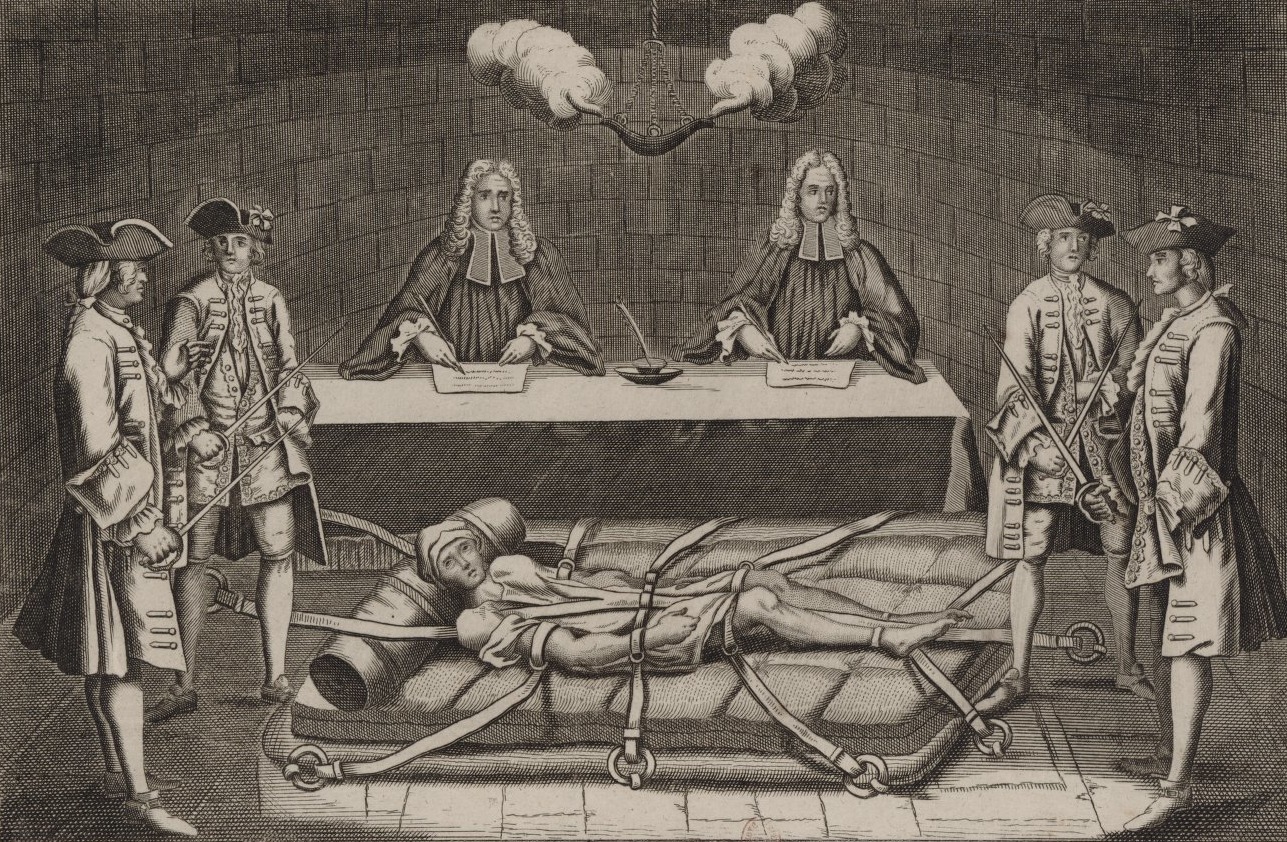

In 1975, the French philosopher Michel Foucault (pronounced foo-coe) published his book Discipline and Punish, where he examined the various systems of punishment that have pervaded France, the first one in the book being the Ancien Regime (there isn’t a t). It was the political system of France from the Middle Ages to the Revolution, where people were publicly hanged, and notably, where Damiens the Regicide was skinned alive, had his hand melted together with the knife he used to commit the crime, was amputated and quartered by horses, and had his ashes thrown to the winds all in the same day. As brutal as it may sound, there is a method to this madness, and its that very method that shares so many similarities with Dr. Phil as a TV show. What I would like to do is to explain how the Ancien Regime worked in detail, according to Foucault, and then, going from there, compare it to Dr. Phil. So, let’s begin.

Before any execution, and before any Dr. Phil show, there is a trial. Now, our trials are (supposedly) fair and humane, insofar as they’re based on evaluating evidence that isn’t hidden from anyone and also based on making decisions democratically (with a jury); in a word, they’re transparent. In no way was there transparency in the Ancien Regime. The trial went on mostly behind closed doors, with the criminal having no knowledge of the evidence being used, the names of the accusers, or even the charges that were being held against them, and judges were allowed to deceive the criminal during questioning. There was no jury, no ordinary citizens who took part in the process. This was because there was a certain knowledge about which punishments where appropriate for which criminals, how much proof was needed to punish a criminal and so on, that the public simply didn’t have, and since they didn’t have that knowledge, they were not seen as deserving to be a part of the discussion.

Part of this knowledge was what Foucault called the “penal arithmetic”, which had the various kinds of “proofs”, whether full proofs (two trustworthy witnesses saying they saw the crime committed), semi-full proofs (one witness), or “adminicule” clues (rumors, how the person acted when questioned, etc.), and how these could be “added” together (two semi-full proofs could make a full proof, a few adminicule clues could make a semi-full proof, and so on). Here, we find another difference. Unlike our system, which is based (ideally, at least) on the maxim, “innocent until proven guilty”, the Ancien Regime knows no innocent suspects. Each of these different kinds of proofs established a different amount of guilt from the start; if there was a semi proof against you, you were semi guilty from the outset, and deserving of some form of punishment.

Because the person was already deemed guilty from the outset, torture was often applied both as a punishment, and as a means of extracting a confession which would justify further punishment. In confessing, the “patient”, the one who was being tortured, would give validation to the decision of the judges, since confession was the highest form of evidence one could have; as Foucualt says, the patient would play the part of “living truth”, where their confession would give further support to the decision already made by the magistrates.

Supposing that an execution sentence was passed, it usually took place in public with an audience to watch. Not only that, but the criminals could be carried in wagons in the middle of the street, have soldiers accompanying them, etc. From the beginning to the end, there was a spectacle to watch; even after the patient was finally dead, their bodies would be left to hang so that everyone could see them.

Why was it so important? Why did the punishment need to be seen at all?

At least in the Modern Era, there has always been an element of retribution in punishment; crime is seen as violating some right, whether against an individual (in cases like theft), or against the entire social body (in cases like protesting), and the criminal must pay for the damage done. But, in every system of punishment, there is always something more. In the Ancien Regime specifically, the law represented the will of the sovereign, and so, no matter how insignificant, any breaking of the law was seen as a declaration of war against the sovereign. This is why there was such a spectacle to punishment, because every crime is a personal attack on the sovereignty, so he has to show himself as ultimately powerful to everyone, he has to crush his opponent, which he does both through excessive torture of enemies, and through the glorious rituals that accompany that torture. The spectacle makes that power manifest to the public.

The power of the sovereign was represented in the executioner, and so, there was a sense of battle in the execution. The executioner confronted his patient, and had to triumph over them, by attacking efficiently, by hitting correctly and by successfully carrying out the sentence. If he was ordered to cut off a patient’s head, and did it in a single blow, his triumph was applauded by the audience; if he didn’t succeed in doing his job, he was thrown in prison.

In the same way the “truth of the crime” was supported by the confession, so it was at the execution. In the most simple sense, patients were forced to read their sentences out loud, but Foucault also talks about the use of “symbolic torture.” Different punishments corresponded to different crimes (hands were cut off of thieves, tongues were cut off of blasphemers, etc.), sometimes the execution was held at the place of the crime and used the very same weapons the criminal used, sometimes people who committed certain crimes had to where certain clothes, etc. All of these formed a set of symbols that gave an impression to the public, making the idea that the criminal had in fact committed a crime more clear and more easy to accept.

The audience is the most interesting part of this ritual, because they played multiple roles. At the most basic level, they were the people who were meant to be affected by the punishment, to be shown the power of the sovereign, so they wouldn’t think of acting against it. At times though, they could identify with this power, in its pure demonstration, by insulting or attacking the criminal, which was sometimes required as part of the sentence. They actively formed part of the punishment that was meant for them to passively watch. And as a third role, they were guarantors of the punishment, they were the witnesses who ensured that it actually happened (if there was an execution held in secrecy, the public often accused the execution of not carrying out the sentence to its full extent). So, these are all the elements of the Ancient Regime in how it dealt with criminals.

Now, on to the show.

Dr. Phil has a few differences, the most obvious one being that there’s no one brutally tortured on the show. That aside, there’s an important structural difference; even if they’re compared metaphorically, there has to be a conflation between the trial, and the actual public punishment. There are many instances in Dr. Phil, where he interrogates someone about something they’ve already done, but it’s never to send them off to some other place, where they’ll be directly punished for it. In the show, the interrogation and the punishment happen both at once.

This leads to the first similarity. Namely, that the interrogation, the show itself, forms part of the punishment of whoever is deemed the “criminal.” In the episode mentioned earlier, Dr. Phil constantly tries to get the father, Bob, to see that what he has done is completely his fault, and that any other way of looking at it is unreasonable. The discussion itself is a punishment, as he’s forced to take responsibility, forced to relive what he’s clearly ashamed of, forced to acknowledge he is the reason his own daughters don’t love him, and forced to see that his current situation, not being able to go anywhere without being being harassed, not being able to keep a house or a job, is completely his own doing. Also, in not being able to see Dr. Phil’s points, he is portrayed both as a fool and a monster at the same time on public television, where millions of people are watching.

There’s also the tendency to the confession. The punishments Dr. Phil gives, but also the “cures” that he produces at the end of the TV show many times, have to be justified somehow. And the best way to justify them, to accept the identity and implicit claims given in the show, is to make a verbal confession. In this particular case, the episode is two parts: one with the daughter, and one with other people who the father had also molested (a step-sister, and others such as boyfriends of each them). Before Dr. Phil brings anyone else in, he goes on a kind of monologue (from minutes 6-8), absolving Kim from any responsibility of what had happened. He says things like, “It’s 100% his fault”, “a father is someone who should protect you, not someone you should need protecting from”, and so on. What’s interesting isn’t the monologue, but what happens after it, as he turns to the father. Here is the following conversation:

Dr. Phil: “Now, tell me I’m wrong.”

Bob: “I’d be a fool to tell you that you were wrong.”

Dr. Phil: “Then, why are you telling her that? (points to Kim)”

Bob: “I can’t do it over again.”

Dr. Phil: “No, but you can own it now.”

Bob: “I did.”

Dr. Phil: “No, you didn’t. You’re saying, ‘there were two of us there, she needs to own her part of it.” She had no part of it, she was a victim; that’s like saying, “there were two of us involved, I went into the bank and shot the teller”, yes, the gunman and the one that got shot. That’s not two people being involved, this wasn’t sex, this was rape. This is a victim here, she’s not involved, that’s why it’s called a crime.”

Bob: “Yes, I know that.”

Bob always admitted to having sex with Kim, but here is where he confesses, and admits to molesting her. In the moment, he finally agrees with Dr. Phil in saying that this wasn’t a consensual relationship, and therefore implicitly supports Dr. Phil’s judgement that has been dominating the episode since the beginning. He is now playing the role of “living truth” that suspects did hundreds of years ago in the Ancien Regime. This confession also justifies further punishment, as it did in the Ancien Regime, since it’s immediately after this dialogue that Kim’s step-sister, Jessica, is brought in to talk about how she was also molested. Bob initially denies that anything happened, but soon comes to admit to a moment where they were both in the shower together. This second confession is then followed by a third punishment, where testimonies of both Kim’s and Jessica’s middle school boyfriends are presented, saying that Bob had asked them to talk about the sexual details of their relationships (Even this part leads to a confessions, as Bob says, “I did talk filthy and I loved it”). It’s as if the idea moving the show is, “if he molested one person, maybe he molested another”, and once it turns out he did, then the thought becomes, “if he molested two people, maybe he molested even more”, and so on. Each confession justifies bringing out another person, and each new person gives further punishment to Bob, by being further humiliated, by being portrayed more as a monster and more as a fool, and now, even as a liar, as he spends a lot of time denying anything happened before he finally comes to admit to it.

We can also see how there are similarities between the show and the trial; in the same way that suspects were deemed guilty from the outset, so is Bob. When Jessica was brought out, it’s not like anyone, not even Dr. Phil, was seriously questioning whether or not Bob had molested her. It was taken for granted. To make this point, we can look at another part of the episode:

Dr. Phil: “What did he say to you when he was doing these things?”

Jessica: “You know you like it; it feels good, doesn’t it?”

Dr. Phil: “(to Bob) Do you remember saying that to her?”

Bob: “I never said that, and yes, I would remember that.”

Dr. Phil: “( to Jessica) How does it feel when the man that is supposed to be protecting you is in fact victimizing you?”

Bob said he didn’t remember saying anything of the sort to Jessica, and said, if he did, he would remember it, implying that he must be innocent. Dr. Phil responds, not by trying to argue with Bob about what had happened or why he doesn’t remember, but instead by turning to Jessica. His question to her assumes that Bob did in fact say those things, so he is presumed to be guilty from the start, and any attempt from Bob to try and establish innocence isn’t even acknowledged. Lastly, in relation to the trial, evidence is dealt with in a similar way; Dr. Phil and his research team have total control over the evidence and which evidence to show as to make a case. There is no jury.

There are also similarities between the show and the actual execution. The show also contains a “symbolic torture”; in the same way there was a set of symbols which gave the public an impression, so it is on the show. Now, these symbols are different in that they aren’t being produced on the literal body of the criminal, but they are still there. The way Dr. Phil phrases his questions, the scenes repeated before commercial breaks, the various audience responses, all of these can validate some ideas about what a person is and what they’ve done, and discredit others.

You could find tons of examples of this in the episode, each quote given so far is an example. But, I think to prove the point in the best way possible, we have to look outside to a more memeable moment.

Take the famous episode with Danielle Bregoli, where she says “Cash me Outside” and notice the reactions of Dr. Phil and the audience. One part in particular is interesting:

Dr. Phil: “What do you say to yourself that gives you the right to take somebody else’s car?”

Danielle: “I’m finna be sly, the fuck you mean? That’s what make me wanna take a bitch car.”

Dr. Phil: “I’m sorry, are you speaking English? Do you have an accent of some sort? (audience laughs)”

Dr. Phil: “So, tell me again, what is it that you say to yourself that gives you the right to take somebody else’s car?”

Danielle: “I don’t say anything to myself, I just say, “Alright, there’s a car, there’s some keys out in front of me, and I know where the car at”

Dr. Phil: “You know where the car at? Did you go to the 5th grade? (audience laughs)”

Danielle is trying to establish herself as being a certain kind of person, but the symbols of the show construe her as being a different kind of person. In the excerpt, Danielle wants to be seen as “hard” or “from the streets.” This identity is displayed through her use of language (saying “finna” instead of “gonna”, saying “I know where the car at”, instead of “I know where the car IS at”, etc.) and through her logic (a logic that says “rights don’t matter, I just like stealing cars, so I steal cars”). Dr. Phil’s questions, “Did you finish 5th grade” and “Are you speaking English right now” are an attack on the way Danielle uses language, mocking it and viewing it as lesser than the way everyone else uses it; the audience also attacks in the same way by laughing at almost everything Danielle says. Since the idea is that Danielle’s use of language is an expression of how she really is, these attacks on her language are implicit attacks on the identity she’s trying to construct. It’s these attacks which serve as symbols that give a different identity to her, impressing on the viewer the idea that what she’s showing is “fake” and that there must be a “real”, different type of person underneath. The “truth of the crime” has been produced.

Obviously, the show functions as redress for an injury; Dr. Phil has Bob on, in order to right the wrong that has been done to Kim, just like any other punishment, but that isn’t all. There’s a second aspect to this punishment that relates to the sovereign. Now, it shouldn’t be surprising that Dr. Phil can be seen as a sovereign; on the show, he has the most knowledge, the most life experience, and is a public figure. He has complete power. Therefore, it also shouldn’t be surprising that he displays this power, that there is a war going on between him and the guests, and that he triumphs over them. He has to remain the sovereign, and so, displays his excess power by destroying anything that is a challenge to it. Dr. Phil constantly has to silence Bob whenever he tries to present an alternate view, and so, puts this view to “death”, along with Bob himself. After every point Dr. Phil makes, the audience applauds, and there’s something noteworthy about that. It’s not just that they’re applauding at the point; no, they’re also applauding at the element of domination, at the host of the show giving the criminal what he deserves.

Similarly, there are two aspects to the audience; as has already been established, their reactions are part of the series of symbols that give support to certain ideas and discredit others. But also, just like the audiences at the old executions, they themselves punish through insults. Every boo they make is a boo at someone, every laugh is a laugh at someone, and so, they actively form part of the punishment which they are meant to passively watch (the same could be said for the audience watching on TV as well).

What seemed at first to be a simple TV show turns out to be a modern day scaffold, with all of its surrounding elements, from the trials and immediate suspicion of guilt, to public punishment and the demonstration of the sovereign’s power, who is aided by the audience. Dr. Phil is the executioner who doesn’t kill.